#2: TIL about how SPACs work

It's like a speedier IPO but more convoluted and confusing and stuff

What are SPACs?

SPAC. This 4-word acronym, if you’ve followed news related to tech or investing recently, have come up a hell of a lot more often.

As in the last edition, so many smarter people have talked about SPAC. I’ll have them explain what SPAC is.

A SPAC (“Special Purpose Acquisition Company”, or “blank check company”), [Chamath] told us, was a new way we were going to help take big tech companies public. Going public is an important moment in a company’s life. … The current way we do it - the IPO (Initial Public Offering) - stinks. (danco)

In layperson’s terms, this means a shell company1 is formed, raises money from investors, IPOs immediately after, finds a late-stage private company, then merges with them so that the late-stage private company is now public. (luttig)

SPACs = Schrodinger’s stock?

Using one of my favorite ways to explain (analogies!), when you buy the IPO of an established company, it’s like buying a new camera box with all the original stuff in it. When you buy a SPAC, it’s like buying only a box with nothing inside, then the seller promises you that he’ll find a suitable camera that you’d definitely love in a set amount of time, but if he fails to do so, you can get your money back.

That basically means buying a SPAC is a bit like buying into a Schrodinger’s cat situation2, except it’s a company rather than a cat, and instead of Schrodinger, it’s some guy who promotes the empty box. This guy is called a SPAC sponsor.

Chamath, a former high-flying FB exec, started the recent tech craze for SPACs in late 2019 when he became a SPAC sponsor and took Virgin Galactic3 public through SPAC.

Generally, the more famous you are, the easier it is to sell things, right? Same rule applies to SPAC. Since his success, a lot of people are trying to do the same thing, including the founders of LinkedIn and Zynga, Peter Thiel and Li Ka Shing’s son, or even Shaquille O’Neal.

How do SPACs work?

So why is everyone dying to be a sponsor and kickoff their own SPAC? To answer this, we may need to first understand how SPAC works. This might get a bit technical, and I’m doing my best to try and simplify it, but I’m failing pretty hard.

Scroll to the next section for a quick tl;dr summary and to jump into discussion.

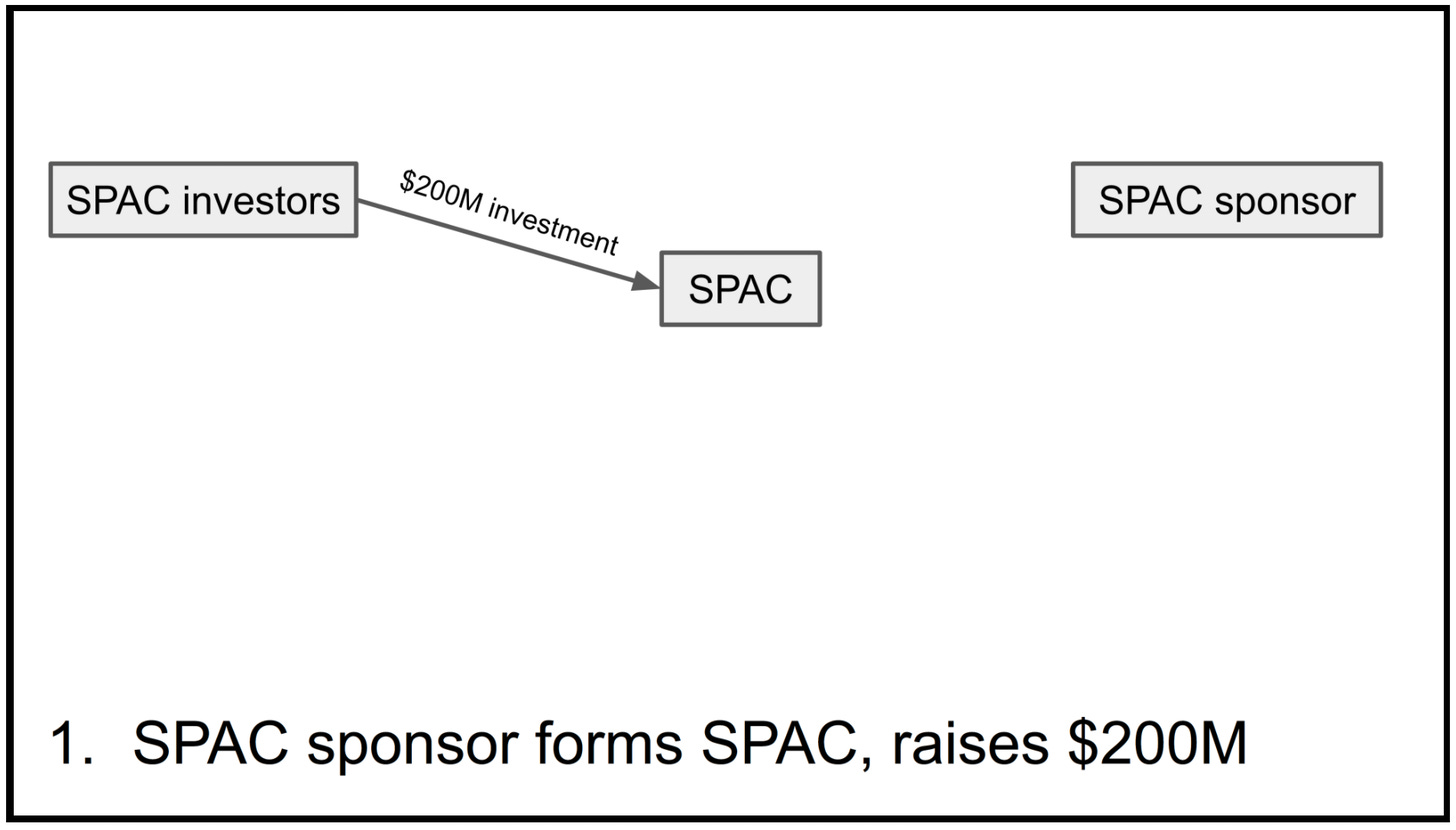

1. Kicking off the SPAC party

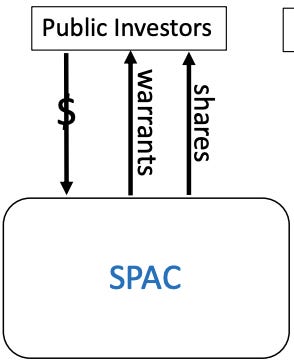

A SPAC sponsor creates a shell company, raises funds from investors, and goes IPO in just a few months.

SPAC investors and sponsors get BOTH shares and warrants4 of the shell company, which are all tradable on the market.

Setting up the company and filing for IPO means expenses, and the SPAC sponsor also puts in 3-7% of the raised capital, while getting “founder shares” in return for free.

The sponsor money covers: IPO underwriting costs and operating expenses (including target company search fees).

Founder shares are usually equivalent to 20% of post-merger outstanding shares.

The IPO process is super fast because there’s really not much to talk about a shell company.5

2. Can anybody.. find me… somebody to SPAC?

The SPAC sponsor promises the SPAC investors that they’ll merge with an awesome company usually in 24 months, accounting for a 4-6 months merger time. This means the sponsor has around 18 months to quickly find a suitable company.

Meanwhile, the investors’ money is kept in a trust that can only invest in safe, short-term US government bonds, up until the merger is completed or 24 months is up. The funds can only be used to:

Execute a merger

Redeem shares6

Investors can redeem shares before a merger is concluded

Note: founder shares can’t redeem shares

3. Target confirmed, lock and load!

4. 3… 2… 1… Houston, should we lift-off…?

Once the due diligence are all taken care of, next comes the most important thing: the sponsor goes to the SPAC shareholders and ask for approval to merge (or “de-SPAC”).

If they reject, the sponsor has to find a new target company before the time is up. When the time is up, then all the investors’ money is returned, and the founders’ shares as well as all warrants are worth nothing.

If they accept, an announcement of the intent to merge is made, and SPAC investors have the option to:

Keep holding the shares and warrants, or

Redeem the shares for the original amount + interest, AND keep the warrants

Therefore, the SPAC investors’ money is essentially risk-free: they get at least the original amount back if the SPAC didn’t work out. If the SPAC was a hit, they can sell the shares at a gain, or redeem it for the original investment amount. They still also get to keep the warrants, which means that even if they redeemed, they still have a potential upside through the warrant.

5. PIPE and it’s done!

The median SPAC redemption is around 73% of the initial capital, which means if you raise a $200M SPAC, and successfully find a merger target, around $150M will be redeemed, leaving you with around $50M to execute the merger successfully.

To get more cash, the SPAC sponsor would find other investors and convince them to invest, executing a private placement or a “PIPE” (Private Investment in Public Equity)7. However, PIPE investors usually do not receive warrants.

For facilitating this transaction, the sponsor gets to charge more money!

Once that’s over with, we can then move on with the merger… or liquidation if the SPAC doesn’t have enough money to get the merger going.

Summary and Discussion

Let’s recap.

Shell company with lots of investor money and free founder shares for sponsor

Sponsor finds a company that wants to go public

Sponsor asks investors for permission to merge with that company

Many investors redeem their money but still gets warrants just in case the company does well

Sponsor finds new investors to replenish the redemption wave

SPAC merges with the company!

It’s like a faster IPO that may be more expensive due to dilution from founder shares and investor redemptions. But for some companies that are riding high on public sentiment, SPACs may be a way to quickly cash in on the hype, like how the EV hype pumped up the stocks of pre-revenue Lucid Motors and Hyliion Holdings, fake-truck Nikola Corp, or fake-orders Lordstown Motors.

Why is it so popular then?

For SPAC investors (dominated by hedge funds): it’s an easy way to park your money for 2 years (essentially risk-free) while getting potentially unlimited upside from the additional warrants received.

For SPAC sponsors: it’s a very lucrative structure that lets you get 20% of a company for really cheap, potentially gaining capital gain and more fees from the ensuing PIPE transactions, giving you a median return of 200%.

Companies: to SPAC or not to SPAC?

For target companies, SPAC is only one way out of many to go public.

Then, why SPAC instead of the other routes?

The certainty of going public.

When you sign the merger agreement, you know you’re going public, and you know the price. You negotiate with one person—the sponsor of the SPAC—and you agree on the price, and then you sign the agreement and the deal is pretty much locked in. You don’t necessarily know how much money you’re raising—how many shares you'll sell—because the investors in the SPAC have the right to ask for their money back if they don’t like the deal. But you’ll at least raise some money, at a fixed price. (Matt Levine)

The speed of going public.

The SPAC is much faster than an IPO or a Direct Listing, which will both take 6-7 months from beginning to end. With a SPAC you could be public in two-months from when you start the process (assuming you have your house in order). (Bill Gurley)

On the flip side, why not SPAC?

The uncertainty of everything else besides confirmation of going public:

When you sign the merger agreement, you know you’re going public, and you know the price. You negotiate with one person—the sponsor of the SPAC—and you agree on the price, and then you sign the agreement and the deal is pretty much locked in. You don’t necessarily know how much money you’re raising—how many shares you'll sell—because the investors in the SPAC have the right to ask for their money back if they don’t like the deal. But you’ll at least raise some money, at a fixed price. (Matt Levine)

SPAC is actually more expensive than an IPO due to all the dilution

Total IPO costs, including the pop, are roughly 20% to 22% of cash raised in in an IPO. … The median SPAC’s dilution amounts to a staggering 50.4% of cash delivered in a merger.

Less than desirable post-merger returns, probably caused by dilution:

Conclusion

SPACs used to be viewed with disdain as a last resort to bring private companies public. However, it’s been on a roll as around 350 SPAC IPOs have occurred in the past 2 years.

SPAC as a financial structure is still a work in progress, as financiers are still looking for ways to improve on this basic framework. For example, check out Bill Ackman’s SPAC that uses a financial concept dating back to 1653 in order to align incentives between SPAC sponsors and all the shareholders.

But then again, IPOs also have their own long history, with a 1922 book titled “Successful Stock Speculation” giving advice on buying IPOs: Don’t.

So who knows, SPACs are still evolving, it may be early days yet for the instrument, and this might be another case where we see a financial innovation beating out many regulators’ slow attempt to provide liquidity to startups in India, Indonesia, and others.

This is a really long post, with lots of details sprinkled in-between that leaves me not a lot of time to put jokes in… but that really says how complex SPAC is, especially for people without any background in finance, and I don’t think I explained it simple enough.

Anyway, that’s it for today but feel free to ping me anywhere you know I might be to ask any questions so that I can explain further, or to correct me on the above so I can go on and fix it.

Shell companies are registered, legal companies with no operations. Like you registering a new Instagram account without posting anything on it. At least you can use it for other things you won’t do with your normal account, like stalking people’s public feeds or stories.

Schrodinger’s cat is a philosophical question where you put a cat in a sealed box with something that might kill the cat, so that before you open the box, you have no way of knowing if the cat is alive or dead. In a way, it can be summed up by Forrest Gump’s “Life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re gonna get.”

Virgin Galactic builds spaceships that took Tom Hanks, Brad Pitt & Angelina Jolie, Michael Schumacher, Stephen Hawking, and other tourists to space. Yes, even Paris Hilton went to space.

Receiving warrants is like receiving the privilege to buy something at a fixed price (“strike price”), no matter what the current price is. For example, if someone gave you a warrant for the rarest Pokemon cards with a $100 strike price, you can buy it for $100 anytime until the warrant expires.

If you do a share redemption, it means that the company buys the share back from you.

Since the SPAC is already a public company, this essentially means that the SPAC issues new shares to private investors (not to the public). It’s like selling your lockdown sourdough bread only to your friends instead of using FB Marketplace or Craigslist.